Editor’s Note: Barbie Latza Nadeau is the Rome bureau chief for Newsweek Daily Beast and a contributor to CNN. She is working on a novel based on the Costa Concordia disaster.

Story highlights

Costa Concordia liner to be rotated upright 19 months after deadly wreck in Italy

South African engineer Nick Sloane, 52, leading the salvage operation off island of Giglio

Sloane: I was hired for risky project because "If something goes wrong, I can be sacrificed"

On a sweltering afternoon in the middle of August, Nick Sloane is chatting with a couple of journalists over beer at an outdoor cafe in Giglio harbor.

Sloane, 52, is the South African freelance salvage master hired by the American-Italian team of Titan Salvage and Micoperi to lead removal operation of the Costa Concordia, the cruise ship that ran aground off Giglio in January 2012, killing 32 people. He is essentially a sub-contractor hired by Costa Crociere, the ship’s owner, which is under the umbrella of American-owned Carnival Cruises. He is wearing his signature white polo shirt from the project – JV Company Titan Micoperi with the logo “Love and Determination” embroidered in blue over his heart.

Sloane is sort of a cross between Russell Crowe and Prince Harry, with the type of red-freckled skin that should never be in the sun. Like one might expect of a man who spends a lot of time in the company of rugged cowboy types, his sense of humor lies somewhere between self-deprecating and sophomoric. He claims he was hired for the project because “If something goes wrong, I can be sacrificed.”

Sloane tries endlessly to tease a blush out of any female in earshot with jokes about how he wants his burly crew to wear pink t-shirts, or quips about his “pole dancers” – meaning, of course, his Polish salvage workers who dance, he says. He is quick to open up the file on his phone or computer marked “blow jobs” with photos of all the ships he has detonated. Some have videos of the fiery explosions.

INTERACTIVE: How Concordia will be raised

He intersperses his salvage war stories with warm family tales about his long-suffering wife of 24 years, who has had to shoulder the responsibility of raising their 17-year-old twins and 10-year-old daughter while he disaster hops around the globe.

His chair, as always, is facing the rusting, rotting carcass of the not-so-luxurious cruise liner slumped on its side a few hundred meters away. No one is talking about the obvious – how the salvage crew plans to roll the massive ship upright in a risky procedure known as “parbuckling” in mid-September.

Instead, the conversation is focused on whether he will ever get to golf at the posh Argentario Golf Resort in Porto Ercole on the Italian mainland across the sea from the island. Sloane, who describes himself as a passionate, albeit “not so good” golfer, had hoped to be back home in South Africa by the first week of September to play a round at his beloved Erinvale Golf Club. But bad winter weather and burgeoning Italian bureaucracy have kept him captive on the island for a little bit longer.

“I can’t leave the island for good until she does,” he tells CNN, nodding to the ship in front of him. “We are here until the job is done.”

READ: What’s inside of wrecked cruise ship?

Sloane, who had hoped to tip the ship on the 4th of July – complete with a fireworks display – says when the Concordia does leave Giglio harbor for good, he will be on a makeshift bridge on the top deck. Because the ship will be towed, no one will be at the helm per se. But Sloane, who has a master mariner certificate that allows him to sail any ship of any size anywhere in the world, will be the de facto captain when it sets sail on its final voyage.

Unlike the Concordia’s original Captain, Francesco Schettino, who wrecked the massive ship on Giglio then allegedly scampered ashore leaving thousands of passengers to fend for themselves, Captain Sloane says he will be the last one off when it reaches its last port of call, likely Piombino or Palermo, where it will be dismantled.

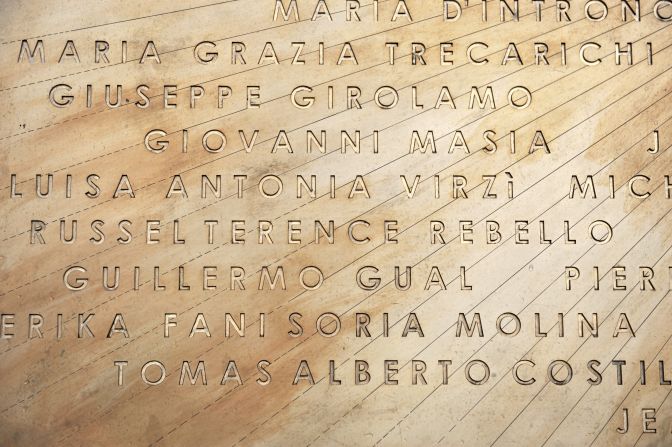

As usual with Sloane, the mood is light and jovial – until he gets a text message. This time it’s not an urgent call from a dive manager or engineer working off shore on the ship. It’s from Kevin Rebello, the brother of a waiter on the Concordia who is one of the two missing passengers whose remains are presumably still pinned between the massive hull and the rocks the ship rests on.

The message is in Italian, a language that Sloane hasn’t quite mastered beyond salutations and his favorite phrase, “poco-poco,” which means “just a little bit.” He looks visibly concerned. He passes the phone around for translation. It’s a simple message wishing him a “happy ferragosto” – the mid-August national holiday that has been celebrated in Italy since the emperor Augustus introduced it in 18 B.C.

Sloane seems relieved that it was a cordial greeting. It’s clear not all of his conversations with Rebello have been easy. “I hope we find him,” Sloane says, referring to Russel Rebello’s remains. At times, it is almost as if Sloane is working for the victims, not the company who hired him to remove the ship.

READ: Has master mariner in charge of salvage met his match?

Sloane is very aware of the ghosts of the Costa Concordia. In the early days of the salvage operation, he spoke about how seeing the personal belongings from passengers floating in the waters bothered him. And Sloane isn’t a man who is easily bothered. He is used to dealing with toxic cargo containers and burning oilrigs, not floating champagne bottles and fancy tableware. He is also very aware of those who died, and those who are still missing. One of the many reasons Sloane’s team couldn’t use explosives to blow up the ship – a far easier way to get rid of crippled vessels – is because of the victims still trapped under the hull. “She is a graveyard in many ways,” he says. “We don’t ever forget those who died trying to get off the ship.”

In fact, one of the few times Sloane has ever paused the 24/7 salvage schedule of his 500-strong crew since taking over the wreck site in June 2012 was on the one-year anniversary of the accident last January. He used one of his tugs and a small crane to return a symbolic section of the 96-ton boulder lodged in the bottom of the Concordia back to the sea. After the tearful ceremony at the point of impact just 450 feet from Giglio’s shoreline, the ferry carrying family members of the ship’s 32 victims stopped in front of the sunken vessel to throw wreaths into the water. Sloane and his crew, including the underwater divers, stopped their work to salute the mourners.

Most ships from Sloane’s impressive resume of catastrophes have involved vessels on fire, crippled cargo ships or leaking oil freighters. He was involved in managing the cargo recovery operation during the rescue of the Brillante Virtuoso tanker that was attacked and set alight by pirates off the coast of Yemen. He also worked on the Jupiter-1 oil rig that sank in the Gulf of Mexico. The Concordia is the first passenger vessel he has worked on, and the first wreck where more than a few people died, although the biggest human tragedy he has been involved with was the 1987 deep sea recovery of a South African passenger plane called the Helderberg, which caught fire in flight and went down off the island of Mauritius, killing 159 people.

Sloane often gets emails from Concordia passengers asking him to look for belongings in the ship’s sunken staterooms. The salvage team is not allowed to enter the ship’s sleeping quarters (all their operations take place outside the ship) so Sloane often ends up describing the salvage procedure to explain why they can’t search for personal effects.

READ: Has master mariner in charge of salvage met his match?

In a letter to former crew member Dan Theodor, shared with CNN, Sloane explained how hard it would be to retrieve any missing items. “I am sorry that we cannot go inside the ship to look for your laptop,” Sloane wrote to shipwreck survivor. “But it is still on its side and remains a dangerous place to try to access.”

Sloane has also endeared himself to the islanders. He cannot walk down the main street of Giglio without being stopped a dozen times to shake hands or share a joke with the locals who now consider him one of their own. Few people have a better gauge on Giglio than Trudy Brandaglia, an Australian who has lived on the island for 50 years. As the owner of Brandaglia real estate and rental agency she was one of the first to meet him when he arrived last year with his family looking for a place to live.

“He is a gentle, extremely polite, educated, discreet, hard-working experienced man with a load of responsibility, yet always ready to help others and with a smile for everybody,” she told CNN. “In short, a gentleman personified. Giglio is lucky to have him and the people working for him as well.”

But Sloane is not a typical expat. After more than a year on the island, he has honed in on his favorite Italian specialties: spaghetti with clams and Antinori Cellar’s signature super-Tuscan “Tignanello” which he prefers far more by the bottle than by the glass. But his Italian stint is short, and he never had dreams of living Italy, which separates him from many foreigners who live in the country.

Instead, Sloane is on the job in much the same way a soldier goes to a war posting. The location is not by choice and, as such, is almost inconsequential. You either eat and drink in the crew’s floating canteen or dine among the locals on shore. He knows first-hand that Giglio is hardly a tough duty station. His next job could take him to somewhere far less idyllic.

In fact, most of Sloane’s previous salvage operations have taken him to much rougher places around the world. Sloane has worked in Pakistan, Yemen, Papua New Guinea and Mexico in all sorts of tough conditions, both metrological and political.

He began his career as a mariner in the salvage division of the South African shipping giant Safmarine in 1980, but after a shipboard fire piqued his interest in maritime salvage, he transferred to the salvage and rescue division and quickly moved up the ranks to become a salvage master. The first salvage operation he led was on the Brazilian break-bulk carrier Rio Assue that caught fire in the South Atlantic. He then spent a period working on pipeline projects before heading up salvage operations in South Africa for Smit Salvage, which was tasked with defueling the Costa Concordia before he joined the team.

READ: What cruise lines don’t want you to know

Sloane was working on the Rena oil spill disaster off the coast of New Zealand in 2011 when he got a call from Titan Salvage boss Richard Habib – himself a legendary salvage master made famous among mariners for big jobs he led, including saving the Cougar Ace, which nearly sank off the coast of Alaska in 2006 with 4,703 Mazda cars on board.

Sloane had seen the wreck of the Concordia in news reports and couldn’t say no to the challenge. He describes meeting the team “sweating in a suit” at an awkward dinner at which few words were spoken. He says he broke the ice by skillfully ordering the best food on the menu.

Sloane is one of those rare sources whose charisma offsets the mind-numbing technological details about things like caissons, strand jacks and water glass. He is also a challenge for Costa’s public relations people, who have had to corral him in to have more control over the message about the company’s dedication to cleaning up the Concordia.

In the early days after the salvage operation began, Sloane would simply tell it like it is – including the risks and challenges he and his team faced saving the Concordia from the bottom of the sea. He was all too happy to commandeer a tug and take any curious journalist with a notebook or camera around to see the ship up close and personal. But as the salvage operation reaches its critical stage, Costa is ever more mindful about putting a positive image on its delicate operation. They are just as aware that Sloane is about the best good-will ambassador they could hope for on a project with an eyesore that is hard to dress up and make pretty.

“Nick is a real leader both in life and at work. He is very professional and friendly at the same time,” said Mina Piccinini, head of communication and sustainability at Costa Crociere, whose daunting task has been to put a positive spin on how Costa has taken responsibility for the accident. “He is loved and appreciated both by the islanders and by the members of the team. Journalists define him as ‘charismatic Nick.’”

Eventually the Concordia will be a distant memory for the people of Giglio – and once the ship and those saving it have left, they will try to return to normal, though the island will forever be scarred by the disaster.

“It’s more likely we would name a street after Nick Sloane than the Concordia,” Giglio Mayor Sergio Ortelli told CNN. “We would always welcome him back, but hopefully for a vacation next time – not for another shipwreck.”

READ: How cruise ship tragedy transformed an island paradise