Editor’s Note: Beverly Daniel Tatum is the president of Spelman College in Atlanta and the author of “Can We Talk About Race?” and Other Conversations in an Era of School Resegregation. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

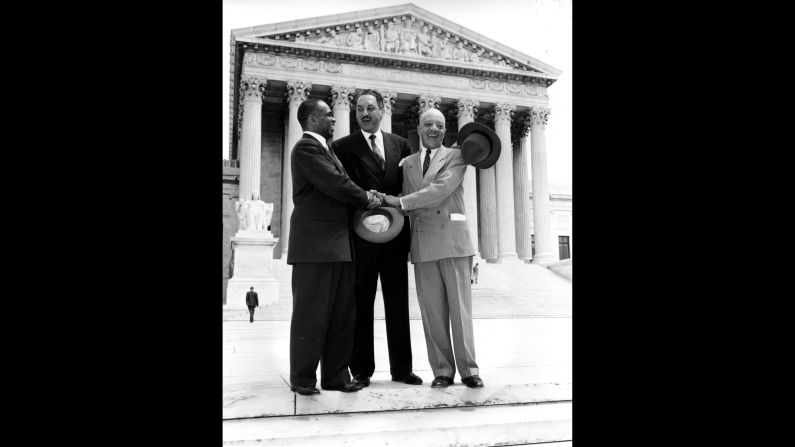

The 60th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education is May 17, 2014

The Supreme Court case desegregated public schools

Public schools are again segregating along racial lines

Spelman College president: We fail to address school segregation at "our own peril"

I was born in Tallahassee, Florida, in 1954, the year of the landmark school desegregation case, Brown v. Board of Education.

The struggle for integration has shaped my life from the very beginning.

When my father, an art professor at Florida A&M University, sought to pursue his doctorate in art education at Florida State University, the state of Florida chose to pay his transportation to Penn State rather than open its doors to an African-American graduate student.

In 1957, he completed his degree at Penn State, and in 1958 became the first African-American professor at Bridgewater State College, now Bridgewater State University, in Massachusetts, where I grew up. My parents were part of the great migration, moving to the North to escape segregation.

They achieved their goal. My three siblings and I attended predominantly white public schools in our small Massachusetts town without protest or high court drama, and graduated well-prepared for the colleges we all attended.

Forty-four years later, in 2002, my husband and I left Massachusetts and returned to the South – initiating our family’s reverse migration.

Eventually our sons, and even my parents, moved to Atlanta, too. They returned to a region very different than the one they remembered. Fifty years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, their choice of housing and their freedom of movement are unencumbered by race.

But 60 years after racial segregation was outlawed in schools, public education is again segregating along racial lines. And not just in the South, but across the United States.

Schools are more segregated today than in the 1980s, according to a new report released by researchers at UCLA’s Civil Rights Project, “Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and Uncertain Future.”

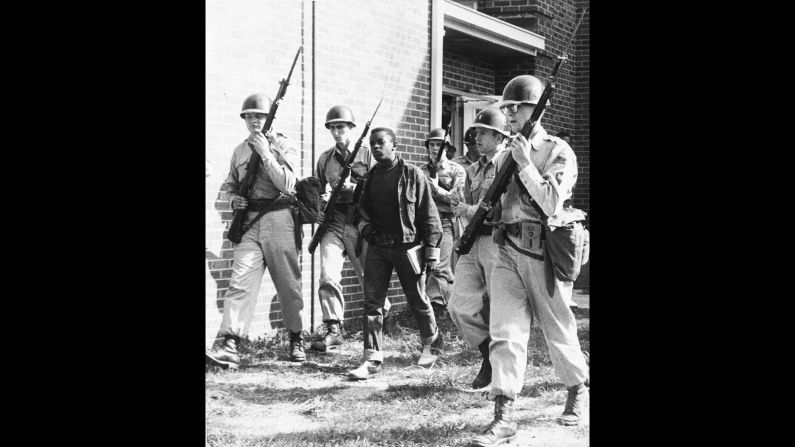

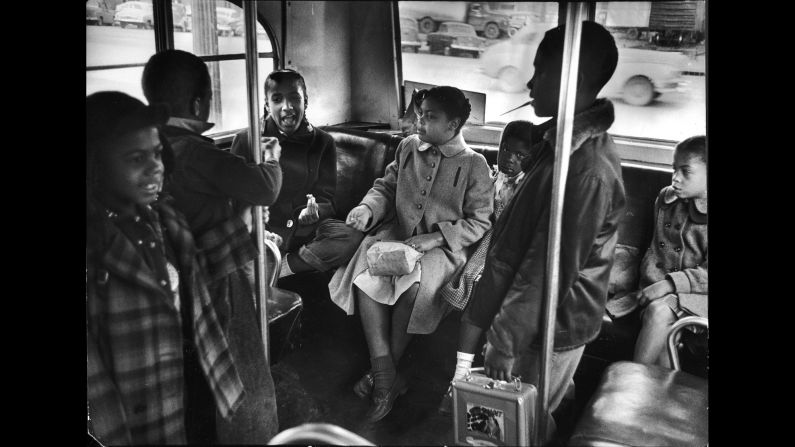

This is the result of continued patterns of residential segregation, and a series of Supreme Court decisions that have quietly undermined the implementation of Brown through a shift away from court-ordered busing and other mandated desegregation strategies.

As school districts move back to “neighborhood school” policies, white students will likely have less school contact with people of color than their parents had. Particularly for young white children, interaction with people of color is likely to be a virtual reality rather than an actual one, with media images (often negative ones) most clearly shaping their attitudes and perceived knowledge of communities of color.

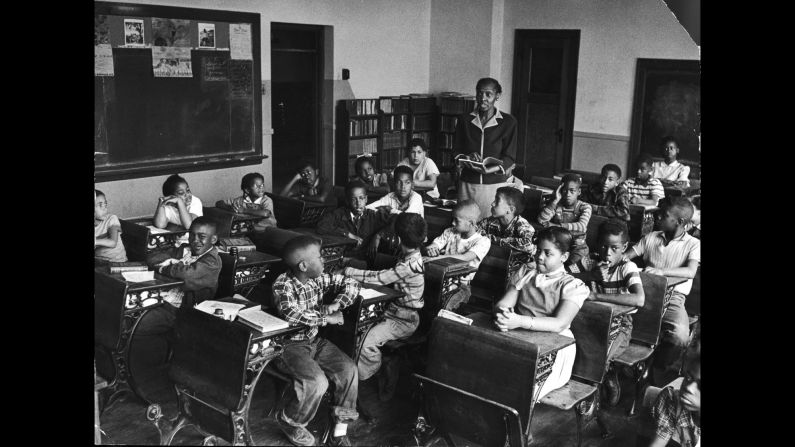

For students of color, the return to segregation means the increased likelihood of attending a school with limited resources. Most highly segregated black and Latino schools have high percentages of poor children. At most highly segregated white schools, middle-class students are in the majority.

The negative educational impact of attending high-poverty schools is well-documented.

Whether a student comes from a poor or middle-income family, academic achievement is likely to decline if the student attends a high-poverty school.

Conversely, academic performance is likely to improve if the student attends a middle-class school, even if his or her own family is poor. The learning conditions which are taken for granted in middle-class suburban schools are too often absent in impoverished classrooms.

It is not surprising that the outcomes associated with high-poverty schools across the country are bleak: lower test scores, higher dropout rates, fewer course offerings and low levels of college attendance.

If we remember that the original impetus for the Brown lawsuit was not simply a symbolic fight for the acknowledgment of the equality of all children, but a struggle for equal access to publicly funded educational resources, we can see that the struggle continues.

So, what must we do?

In particular, white children will need to be in schools that are intentional about helping them understand social justice issues like prejudice, discrimination and racism, empowering them to think critically about the stereotypes to which they are exposed in the culture.

Such tools are needed to help them acquire the social skills necessary to function effectively in a diverse world, and are essential for continued progress in a society still struggling to disentangle the racism woven into the fabric of its founding.

The hopeful news is that there are educators around the country working hard to create anti-racist classrooms and learning environments even when their classrooms are predominantly white.

Children of color in under-resourced, racially isolated schools also need these same tools. But they will also require powerful advocates to insure that they have committed and well-trained teachers, a challenging curriculum and the educational resources needed to inspire their own striving for excellence.

Providing these resources equitably is a daunting task, one that has never been accomplished in the history of education in the United States.

Yet we fail to do it at our own peril.

In 2014, the question we all must ask is: How do we build strong school communities where every student, regardless of race, is supported to achieve his or her personal best, and teach the skills needed to live in healthy, democratic society?

When we can answer that question, the promise of Brown v. Board of Education will be fulfilled.

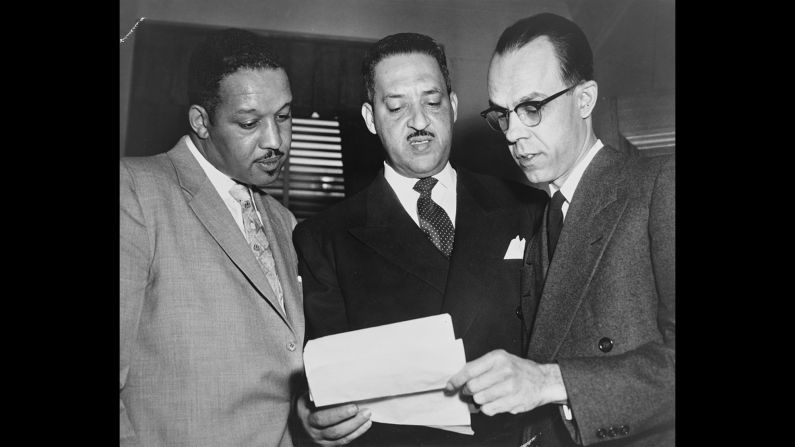

![One of the key pieces presented against segregation was psychologist Kenneth Clark's "Doll Test" in the 1940s. Black children were shown two dolls, identical except for color, to determine racial perception and preference. A majority preferred the white doll and associated it with positive characteristics. The court cited Clark's study, saying, "To separate [African-American children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone."](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/140516160638-08-brown.jpg?q=w_2000,h_1125,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)