African Voices is a weekly show that highlights Africa’s most engaging personalities, exploring the lives and passions of people who rarely open themselves up to the camera. Follow the team on Twitter.

Story highlights

Filbert Bayi is a middle distance athlete from Tanzania

He set a world record for the men's 1500m at the 1974 Commonwealth Games

Today he is helping mold his nation's next generation by establishing education facilities

He says: "I would love to see one of my students to be president of this country"

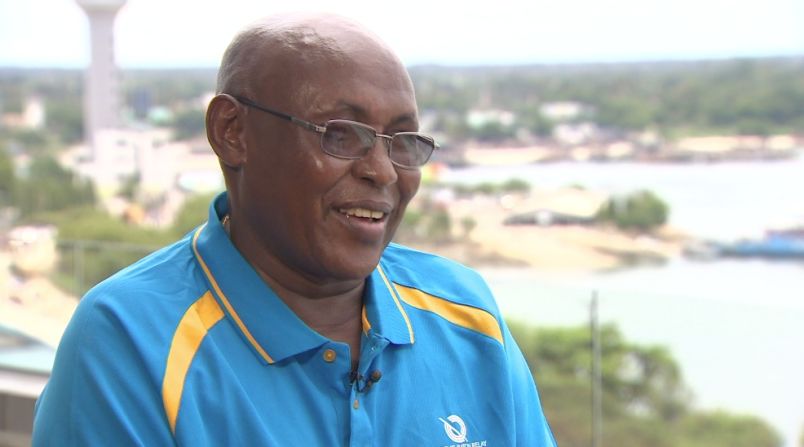

He’s smashed world records and revolutionized running during his illustrious career. And yet the name of Filbert Bayi has almost been forgotten.

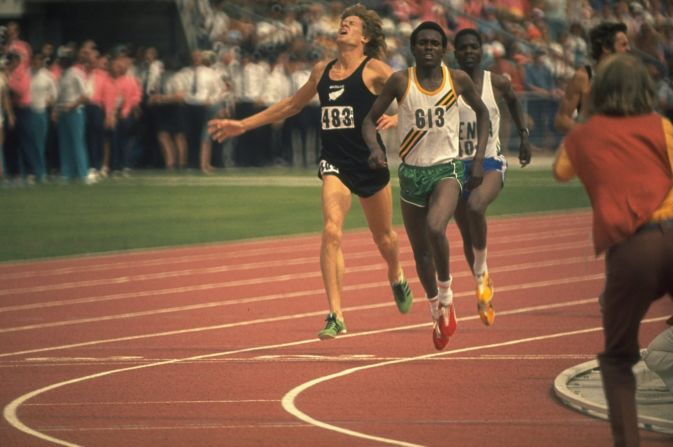

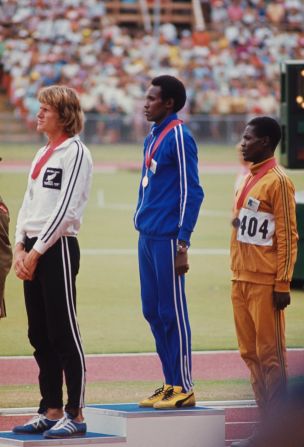

The date was February 2, 1974 and the stage was the men’s 1500-meter final at the 1974 Commonwealth Games in Christchurch, New Zealand. Leading from the start, Tanzanian Bayi continued at a blistering pace throughout the race to cross the finish line first in a race that’s often described as the greatest middle distance event of all time. His record-breaking time? Three minutes and 32.2 seconds.

It would take five more years for Great Britain’s Sebastian Coe to break that achievement. Today, 40 years on, Bayi’s phenomenal performance remains a Commonwealth record.

“I changed the system of running,” Bayi tells CNN. “In those years before I broke the record, most of the athletes were running in the group, waiting for the last 200 meters and sprint.

“I changed the whole system [and] ran from beginning to the end. Very few people appreciate that. Just because I didn’t win a gold medal in the Olympic Games but still my [Commonwealth Games] record stays for 40 years.”

Tanzania’s most decorated athlete was born in the Rift Valley – a region renowned for producing some of the world’s best runners. He says the area’s high altitude and farming lifestyle cultivate the skills required for long distance running.

From cow herder to track superstar

“My parents were farmers, cow herders. When I was a kid, I used to take care of the goats or cows,” he explains. “And up there in the bush, you do hunting, running with the dog, running with the animals and running with the cows and all that, I think, made me built me some stamina.”

In 1961, at the age of six, Bayi started school. Its location was two miles away from where his family lived.

“So every morning I had to run to school, then I had to go back for lunch. Then I had to go for afternoon classes. So you can imagine I ran about eight miles a day. That made a lot of stamina in my body.”

Through his years at primary school, Bayi continued to excel as an athlete immersing himself in competitions and working his way up to regional and then national competitions in the hopes of being like his idol, Kenya’s two-time Olympic gold medalist Kip Keino.

Bayi continued his training in the 1970s but he found training in a group a grueling endeavor, especially when he would get inadvertently caught on the spikes of other athletes’ shoes.

“Your life is in danger when somebody spikes you. I thought the only way to avoid spiking was to run from the beginning in front of everybody,” Bayi recalls. “I think I caught some of the athletes with that because they thought I would get tired.

“They made a bad judgment. They said they’ll get me next time but next time the same thing and I always say ‘Follow me, catch me if you can.’”

Coaching Tanzania’s future talent

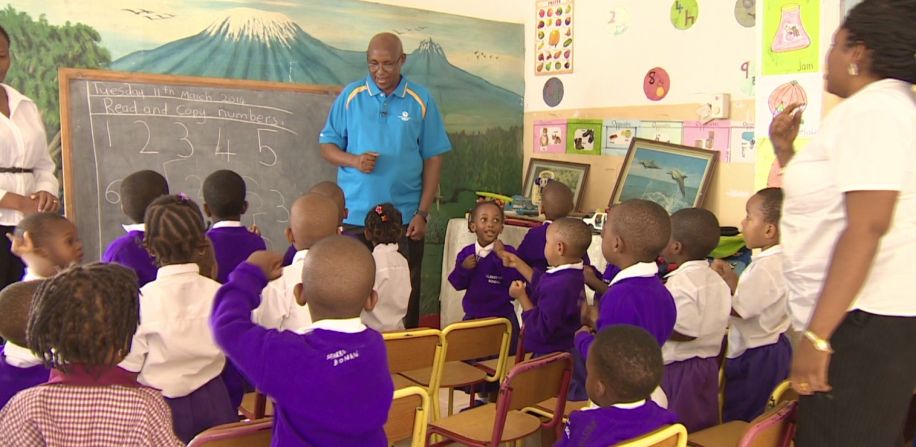

These days Bayi tends to keep off the track and instead focuses his attention on a lifelong dream – to run his own schools and nurture young sporting talent from his homeland.

With the help of his wife, the former middle distance runner opened the first iteration of the “Filbert Bayi School” in a garage with just seven children in attendance. The school continued to grow and by 2004, it had developed into a large campus catering to 1,300 students from nursery-level up through primary school and into secondary education.

Bayi says: “You know sometimes I sit together with my wife and we can’t believe this. It’s a miracle.”

Not content with the education opportunities he has provided to the surrounding communities, Bayi has now set his sights on the next goal – to open a university.

“One day I will have a university maybe, college where I can teach doctors or engineers in that school,” he says. “Or maybe we’ll be expanding the institution to be a big sports academy where we can receive even foreigners.”

Meanwhile, Bayi continues to use his strong track record as a means of inspiring his students.

“Most of the students, they want to be professionals,” he says. “They want to be IT people, they want to be pilots, doctors, be everything. We always tell them, if you want to be anything you have to work hard because those things won’t come like a dream,” he adds. “You have to work hard, you have to commit yourself.

“Most teenagers don’t think about the future, they think about now. So we always teach them, now will pass and then the future will come. And if you aren’t prepared for the future you’ll end up nowhere.”