Editor’s Note: Val Lauder, a former reporter for the Chicago Daily News and lecturer at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is the author of “The Back Page: The Personal Face of History.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely hers.

Story highlights

A lone American reporter, working for the AP, broke the news of the end of World War II in Europe

Val Lauder: For Edward Kennedy, the scoop destroyed his job and drew condemnation; but finally there's an apology from the AP decades later

There’s breaking news, and then there’s BREAKING NEWS.

Some is shock to the system: Think 9/11. Some is anticipated in a way: Think election nights. Each poses challenges to the editors and reporters covering the stories

And then there’s the famous – infamous – AP bulletin.

Edward Kennedy’s “scoop from hell.”

It moved on the Associated Press wire on Monday, May 7, 1945, at 9:36 a.m. EST, 8:36 Chicago time.

When I arrived in the city room of the Chicago Daily News a little before 9 – neither an editor nor a reporter, but a copygirl – the editors were already gathered around the horseshoe-shaped copy desk editing it.

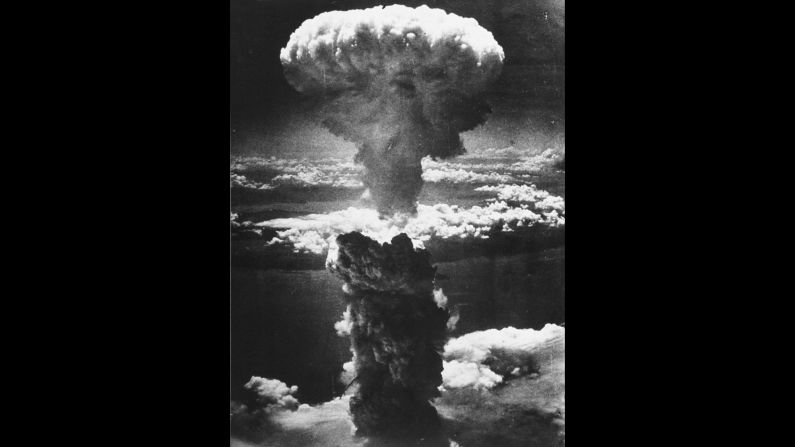

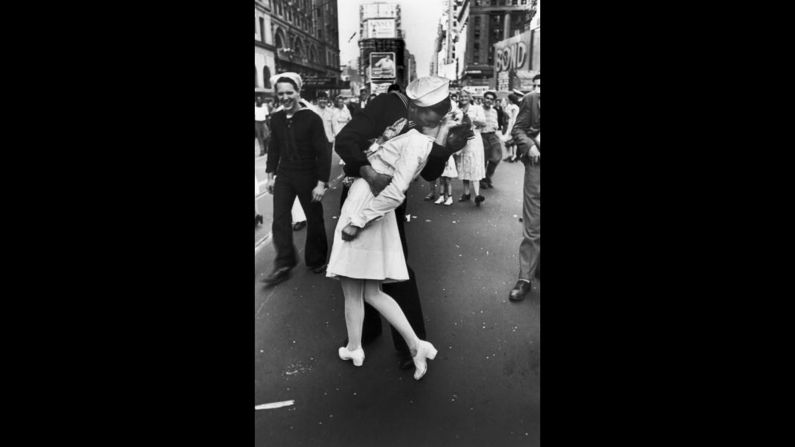

The Germans had surrendered.

The war in Europe was over.

Hallelujah!

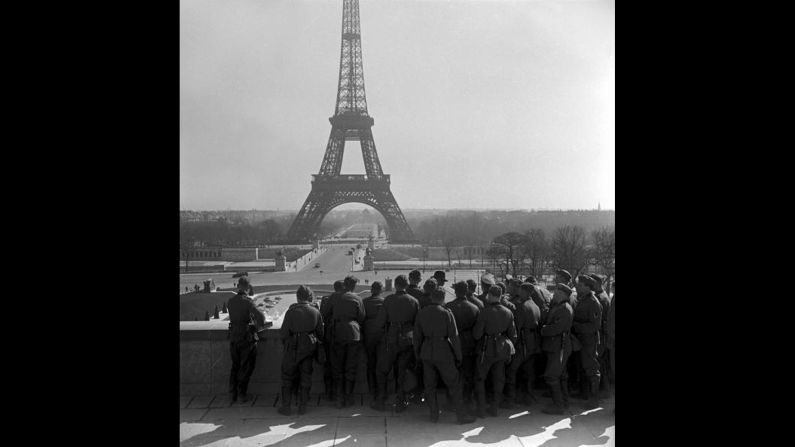

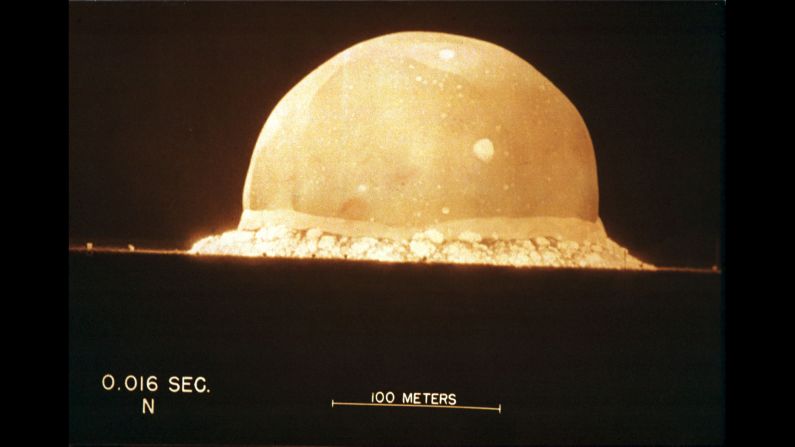

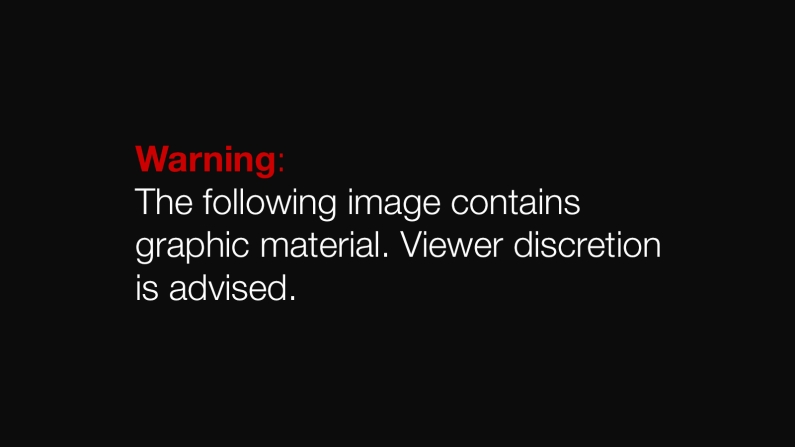

The fighting might still be raging in the Pacific, the island-hopping campaign having many an island to go before the Allies got to the big one: Japan. But the war in Europe was over.

Then someone asked, “Where’s UP?” United Press, the other major wire-service. Where was its bulletin?

INS (the International News Service). Reuters. The networks – CBS and NBC (radio only then) – The New York Times, our own renowned Chicago Daily News Foreign Service. Where were their bulletins?

Every man there knew a false report of the German surrender in World War I caused a premature celebration of Armistice Day – a cable sent by the United Press.

They asked Telegraph Editor George Dodge to call AP. It stood by the story.

‘We’ll go with what we know’

The editors, having given up any thoughts of an EXTRA, faced a scheduled deadline: 10:30 – absolute, nonnegotiable, fish-or-cut-bait time. And a headline was a customary thing.

City Editor Clem Lane said, “Let’s tell ‘em what we know. AP says …”

Executive Editor Basil “Stuffy” Walters had to make the call. He weighed it, nodded. “OK. We’ll go with what we know. The Associated Press says ….

And that’s what they did. They put a kicker on it – to the left, above the headline, a newspaper item for what sets up a headline

The Associated Press says

GERMANS SURRENDER

The phones on the city desk started ringing as word got out – apparently, the Germans had broadcast word of the surrender to their ships at sea – and people were calling to see whether it was true. But we didn’t know.

The morning wore on with conflicting reports.

It’s over … or is it? Now it’s true … no, it’s not. The biggest story in the world was … what?

Finally, in an afternoon edition, the story from AP.

Here’s What Happened In Mix-up on V-E Day

PARIS – AP – The public relations division of Allied Supreme Headquarters today suspended filing facilities of the Associated Press in the European theater until further notice.

Brig. Gen. Frank Allen Jr., chief of the division, addressed this order to Edward Kennedy, chief of the Associated Press Paris bureau.

“The Associated Press is suspended from filing copy by any means in this theater (European Theater of Operations) effective 1640 hours (9:40 a.m. Chicago time) this date, until charges are investigated in connection with the filing of a story under Reims dateline that SHAEF had officially announced the unconditional surrender of all German forces as of 0241 hours this date.”

It was signed by Allen, and paragraph after paragraph followed, parsing what was official and what was not.

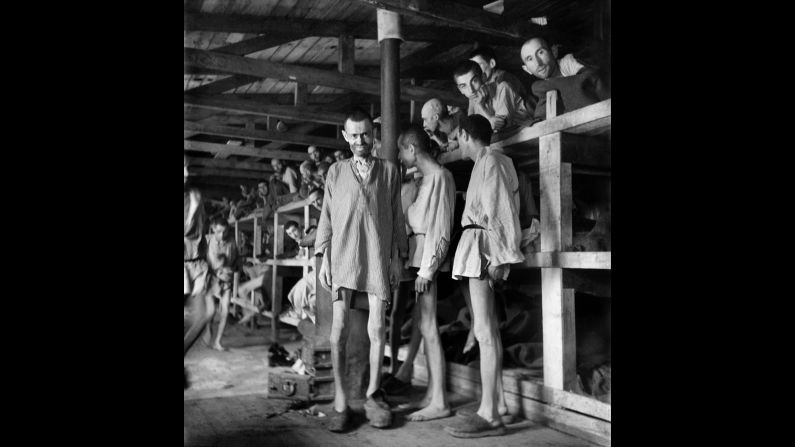

Never disputed: Edward Kennedy had been one of the 16 correspondents invited to witness the surrender and flown to Reims, a city 80 miles east-northeast of Paris. Aboard the plane, Allen, addressed them.

“You represent the press of the world. This story is entirely off the record until the heads of government have announced it. I therefore pledge each of you on your honor not to communicate the results of the conference or the fact of its existence until it is released under the order of the public relations director of SHAEF.” (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force)

On their return to Paris, the AP story reported, Kennedy called The Associated Press office in London and told Lewis Hawkins of the London staff: “That’s official. Get it out.”

“Later,” the story said, “Kennedy inquired of Pitkin (Dwight Pitkin of the London staff) if the copy was moving satisfactorily through censorship.”

Kennedy might have telephoned the London office for a reason. The line from Paris to London was not monitored by censors, but the trans-Atlantic cable to New York was. That’s why Kennedy did not tell the London office that his dispatch was not authorized. They’d have to tell New York, and the censor would pick it up and kill it.

SHAEF not only suspended AP’s filing privileges, it “disaccredited” Kennedy. The Associated Press returned him to New York.

The New York Times story May 8, 1945, wound up in “A Treasury of Great Reporting” under the headline: “News beat or unethical double cross?”

It used Kennedy’s story of the surrender but reported the confusion it had wrought. And it addressed the ethical issue:

“The next day fifty-four correspondents accredited to SHAEF addressed a bitter letter to General Eisenhower: ‘We have respected the confidence placed in us by SHAEF and as a result have suffered the most disgraceful, deliberate, and unethical double cross in the history of journalism.’” Among the signers: correspondents for United Press, CBS and The New York Times.

It said further: “It is clear that had Kennedy refused to promise anything on the plane he would have made certain of missing the great event, which no newsman in his right mind would have done. Later he claimed that he had never promised to keep his mouth shut until it was opened officially and that instead of violating a fundamental tenet in journalism’s code of ethics, he was proud of what he had done. One reporter quoted him as saying that the pledge should not have been exacted and that he did not feel bound by it.”

‘A grave disservice’

The Times wrote in an editorial two days later that Kennedy had committed a “grave disservice to the newspaper profession.”

Time magazine said the incident gave the press a black eye.

The disdain for Edward Kennedy was so great that 15 years later, the CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite, a United Press correspondent in Europe in World War II, refused to stand when Kennedy offered his hand.

When The Associated Press returned Kennedy to New York, it kept him on the payroll but gave him no work to do. In November, he was fired.

He worked as the managing editor of the Santa Barbara News-Press for three years and in 1949, became the associate editor of The Monterey Herald, then its editor and associate publisher.

“Kennedy tried for years to repair his damaged reputation,” said a 2013 article in The Atlantic Monthly. It described the personal essay he’d written in 1948, “I’d Do It Again,” as “a lengthy self-defense.”

“For the gaunt, intense Kennedy,” Christopher Hanson noted in The Atlantic, “it became the scoop from hell.” He wrote a memoir but could not find a publisher. After his death in 1963, the manuscript lay in a box in his daughter’s attic, gathering dust, figuratively if not literally, for almost 50 years.

The AP apologizes

In 2012, Louisiana State University Press published “Ed Kennedy’s War: V-E Day, Censorship & the Associated Press,” edited by his daughter, Julia Kennedy Cochran.

Tom Curley, president and CEO of The Associated Press, and John Maxwell Hamilton, a University Press editor, co-wrote the introduction, saying, the AP “made a kneejerk response to repudiate him publicly to staunch an uproar.”

They also applauded his reporting, concluding, “Edward Kennedy was the embodiment of the highest aspirations of The Associated Press and American journalism.”

Curley issued a public apology for AP’s firing of Kennedy. According to the Monterey Herald, “Curley rejected the notion that the AP had a duty to obey the order to hold the story once it was clear the embargo was for political reasons, rather than to protect the troops.”

The publicity generated efforts to award Kennedy a Pulitzer Prize, posthumously. A story in The Washington Post, November 24, 2012, ran under the headline: “Pulitzer wanted for reporter who broke story on Nazi Germany’s surrender.”

“Ed Kennedy has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize,” The Atlantic said, “honoring him in death for the decision that ended him in life.”

Whatever the merits of giving Kennedy a Pulitzer, 15 other correspondents aboard that SHAEF plane honored the pledge “not to communicate the results of the conference or the fact of its existence until it is released under the order of the public relations director of SHAEF.”

And Edward Kennedy called The Associated Press office in London.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.