“I can’t breathe,” George Floyd said to Minneapolis Police officers on Memorial Day while in custody, with an officer’s knee pressing on his neck. Minutes later the 46-year-old Black man was unresponsive, pronounced dead later that afternoon. Video of the incident then went viral.

Five years earlier and over a thousand miles away in Baltimore, Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old Black man, uttered those same words, “I can’t breathe,” while in police custody, according to trial testimony. Gray died from his injuries one week later.

Many legal experts, including the Hennepin County attorney who prosecutes cases in Minneapolis, drew the comparison between the Gray case and the Floyd case. At the most basic level, in both cases, a Black man was arrested for a minor offense and became unresponsive while in custody. Their encounters both turned out to be fatal.

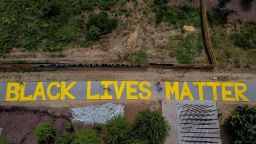

Protesters demanding justice filled streets across the country for days, and within ten days of their deaths the officers involved were arrested.

The Gray case turned out to be a failed prosecution: None of the six Baltimore officers arrested were convicted.

The trial for the four now former Minneapolis police officers, Derek Chauvin, Tou Thao, Thomas Lane, and J. Alexander Kueng, is scheduled for March 8, 2021. While none of the officers have entered formal pleas, Lane’s attorney has entered a motion to dismiss the case against his client and Kueng’s attorney says his client intends to plead not guilty.

As discovery will now begin with legal motions filed and responded to from both sides, CNN asked two attorneys who have already walked this road in Baltimore and other legal experts to offer lessons learned and words of caution.

‘That power of justice is what everyone is screaming for’

On April 12, 2015, Gray was arrested for illegal possession of a switchblade and loaded into a police van that drove him around the city for roughly 40 minutes before arriving at a Baltimore police station. When police went to take him out of the van, he was unresponsive.

Doctors determined Gray’s neck had been broken in a severe spinal cord injury. He died seven days later.

Gray’s death became a symbol of the Baltimore community’s mistrust of police: They blamed the six police officers responsible for his care, custody and control.

On the day of Gray’s funeral on April 27, after several days of peaceful protests, unrest erupted around the city.

One week after the protests broke out, Marilyn Mosby, Baltimore City State’s Attorney, charged the six officers with felonies that, if convicted, could have put some of the officers behind bars for decades.

In defending her office’s actions, Mosby told CNN last month what the message was then: The same as it is now.

“That power of justice is what everyone is screaming for,” Mosby said. “Treat police the same way you would treat anyone else regardless of race, sex and religion, and that’s your obligation.”

Every case ‘has its own set of circumstances’

Defense attorney Michael Belsky, who represented the highest ranking officer charged in Baltimore, Lt. Brian Rice, tells CNN it was “inconceivable that an investigation of this magnitude could be conducted so quickly in a careful and prudent manner.”

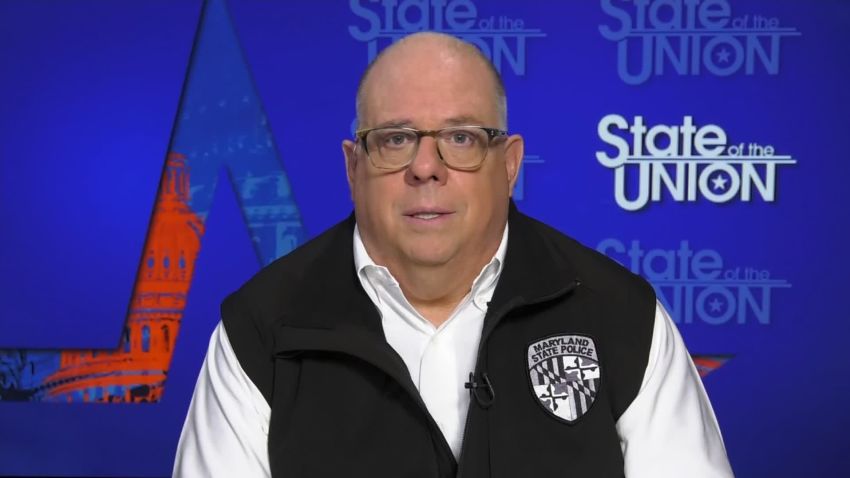

Three days after Floyd’s last breath, under immense pressure to charge the Minneapolis officers involved, Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman was of the same mindset, saying prosecutors in Minnesota did not want to make the mistake that Baltimore did by charging too quickly.

“I will just point to you the comparison to what happened in Baltimore and the Gray case,” Freeman told reporters at a press conference. “There was a rush to charge, it was a rush to justice… I will not rush to justice. I’m going to do this right.”

The next day, Freeman would announce Chauvin’s arrest, but Mosby took issue with his take.

“Saying that there was a ‘rush to charge, a rush to justice’ in the Freddie Gray case is demonstrably false,” Mosby said in a statement.

While there are similarities, legal experts point to one obvious difference between the Floyd case and the Gray case which they say could lead to the conviction of at least one of the former Minneapolis police officers: the dramatic video.

Cell phone video captured then-Officer Chauvin pressing his knee on Floyd’s neck while Floyd was on the ground outside a police vehicle. Floyd repeatedly said he couldn’t breathe and was pronounced dead at a hospital.

“The video is a tremendous difference obviously because we can all look at the video and make reasonable assumptions,” Belsky said. “The biggest difference between the Minneapolis case and the Freddie Gray case is that in the Freddie Gray case there was no video, which led people to speculate both ways.”

But from experience Belsky issues a word of caution: The Floyd case is not a slam dunk.

“Every use of force case is different,” Belsky said. “They are not monolithic cases. Every one is different and has its own set of circumstances.”

Rush for judgment?

Each of the six officers arrested in the Gray case faced at least three charges at trial. All of them pleaded not guilty to every charge.

Belsky’s client, Rice, was charged with involuntary manslaughter, reckless endangerment and misconduct in office.

When she announced the arrests, Mosby stood on the courthouse steps, telling the community “no one is above the law.”

Peter Moskos, former Baltimore Police officer and associate professor in the Department of Law, Police Science and Criminal Justice Administration at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, believes Mosby “heard the cry for justice” five years ago and arrested the officers “to placate the protesters and rioters.”

Moskos says the prosecutor “never showed crime happened.”

“It was a tragedy but it was a civil issue,” he said.

In Minneapolis, ex-officer Chauvin was arrested the day after prosecutor Freeman’s news conference and charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. In the days after Chauvin’s arrest, protests ramped up as the probe continued into the three other officers.

Five days after Chauvin’s initial arrest, those officers were charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder. And Chauvin was additionally charged with second-degree murder.

Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, who had been tapped by the governor to be lead prosecutor, told the Minneapolis community, “I did not allow public pressure to impact our decision making process.”

“We made these decisions based on the facts that we gathered…and made these changes based on the law that we think applies,” Ellison said.

‘The lesson learned is that facts matter’

Because of the lack of video inside the police van there was always a mystery as to what actually happened to Gray’s neck and spinal cord.

Prosecutors asserted it was because Officer Caesar Goodson was driving the van erratically at a reckless speed. But defense attorney Catherine Flynn, who represented Officer Garrett Miller, says the evidence never supported the prosecution’s theory “that he was killed because of a rough ride. There was never a shred of evidence to support that theory throughout all of the litigation.”

That opened up the door for the defense to claim that by intentionally thrusting his head on the van’s walls and by standing up in a moving vehicle Gray himself caused his fatal injuries.

As far as lessons learned from Baltimore, Belsky says Minneapolis prosecutors need to make sure they have a rock solid case.

“The Chauvin case may well be the case where it is more than warranted to charge and secure a conviction. But on the flip side there are cases like the one we had in Baltimore that do not deserve to be charged and where the facts do not support a conviction …The lesson learned is that facts matter and each case is different.”

The evidence just wasn’t there, judge said

The presiding judge for all of the Baltimore officer trials was Barry Williams, a former prosecutor who investigated police misconduct cases for the US Justice Department.

In three separate bench trials, Judge Williams acquitted Rice and Officers Goodson and Edward Nero on all charges, stating as part of the record that the prosecution had “failed to meet its burden to show that the actions of the defendant rose above mere civil negligence.”

Flynn agreed with the judge’s legal determination.

“The judge was extremely thorough and the state’s legal theory simply didn’t hold water,” Flynn said. “They were just wrong.”

Officer William Porter’s trial ended in a hung jury. Prosecutors announced they would re-try his case but then decided to drop all charges against Porter and the two other officers, Miller and Sgt. Alicia White.

“You don’t charge people just to charge them. You charge because you believe a crime has been committed,” said Belsky, Rice’s lawyer. “You want to make sure you do a thorough investigation so that ultimately you can get a conviction.”

Mosby told CNN prosecutors were hindered because Baltimore police “were working against us,” and that “search and seizure warrants weren’t executed.” Baltimore Police have not responded to her claims.

Mosby said that regardless of the outcome of the criminal cases in Baltimore, much good came from the prosecutions.

“We have tangible reforms that have come about as a result of those charges,” Mosby said. “Police officers are mandated to seat belt all prisoners. They’re mandated to call a medic when requested. There is an affirmative duty and responsibility for colleagues if someone crossed the line, for them to go and inform folks about that.”

And as far as advice to the Minnesota defense attorneys who are beginning their journey as the Baltimore attorneys did five years ago, Belsky says: “You have to recognize that there is a community that is legitimately hurt and distrustful of the police and you have to understand that and appreciate that.

“Don’t try to change a community’s perception based on a case. Worry about the facts of the case.”