Story highlights

Doctors obligated to "prevent misuse of medication," position paper says

16% of the population of some high schools and colleges may use "study drugs"

Drugs that work well for kids with ADHD may have negative side effects for healthy children

Pediatrician and neurologist Dr. William D. Graf has noticed a disturbing trend. Over the past 20 years, he begun to hear stories of an increasing number of doctors who give perfectly healthy children prescriptions for the sole purpose of enhancing their focus or memory.

The dramatic increase in the number of children taking stimulants and other “study drugs,” as they are popularly known, seems to back up his anecdotal evidence.

Inspired by his growing concern over this trend, Graf collaborated with five other doctors to write a position paper that offers guidance to physicians and discusses the ethics of the practice. Published Wednesday in the American Academy of Neurology’s journal, the paper is the first of its kind to focus solely on prescribing these drugs to healthy children, Graf said.

“It wasn’t clear to any of us why this hasn’t been written before,” Graf said. “The trend has been around for a couple decades now. It was clear to us that there needs to be this kind of conversation with physicians.”

The paper argues that doctors have a “moral obligation” to “prevent misuse of medication.” It concludes that the practice of “neuroenhancements” isn’t justifiable. It adds that the prescription of these drugs is inadvisable because of “numerous social, developmental, and professional integrity issues.”

“We are a highly competitive society, and we know some physicians are prescribing these at a parent’s request,” Graf said. “Other parents have told us they felt doctors pushed these drugs on their children.”

Though the drugs are effective in treating problems like attention-deficit (hyperactivity) disorder in healthy children, they can have serious side effects like cardiac risks, and taking them can be addictive.

“This is not what these drugs were designed for, and doctors can be a part of the problem,” Graf said. “Our professional integrity is at stake.”

Graf said the number of prescriptions written for these kinds of drugs has increased tenfold in the past two decades. According to a 2004 study (PDF), in some U.S. school districts, “the proportion of boys taking methylphenidate exceeds the highest estimates of the prevalence of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder.”

Another study (PDF) suggests that about 16% of the population of some high school and college campuses uses prescription drugs as study aids.

“Many students think there’s a magic pill that could fix everything. Trouble is, that’s not true,” said Greg Eells, associate director of Counseling and Psychological Services at Gannett Health Services at Cornell University. He believes that when the law changed to allow pharmaceutical companies to market directly to the public, an entire generation’s acceptance of taking prescriptions changed. “It did make a huge difference in self-diagnosis.”

College students take ADHD drugs for better grades

Eells has seen an uptick in the number of students taking or asking for the drugs at Cornell, an Ivy League school known for its rigorous curriculum and ultracompetitive atmosphere. His clinic puts students through a rigorous battery of tests to make sure they actually have ADHD before they receive a prescription for the medication.

Still, he knows that if students can’t get the drugs at his clinic, they may try to buy them from their peers. That’s why he warns students that buying prescription drugs from other students is illegal and dangerous.

“They have a tendency to think if they can Google it, they know what they are getting into,” he said. “But there’s a reason only people who’ve gone to medical school for a long time can prescribe these drugs. These drugs are serious business.”

Dr. Mark Wolraich, chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical practice guideline subcommittee on ADHD, says this newly published position paper represents “pretty much the position that all clinicians have.” His only concern is that parents who hear about it may be too nervous to seek treatment for their children with ADHD, for whom the drugs would actually be beneficial.

“They can work really well with kids with ADHD,” Wolraich said.

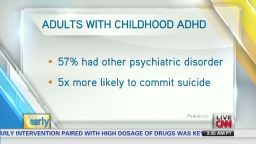

He also notes that there may be more valid reasons for the growing number of young people taking ADHD medicines. More people are being legitimately diagnosed with the disorder, and doctors have changed their thinking about ADHD, he said. Until recently, many doctors believed that children eventually outgrew ADHD symptoms.

“We used to think it disappeared at puberty, but it’s not the case. So there will be more cases of adolescents and people at older ages diagnosed with ADHD,” Wolraich said.

As neuroenhancement grows more popular and new drugs become readily accessible, Graf said, he and his colleagues wondered whether their paper would it still be valid 20 years from now.

“Some have argued this practice is not going to stop. Neuroenhancement is going to continue regardless,” he said. “But we came to the conclusion that I think we should draw line at this practice. We don’t believe that will change.”