Story highlights

Centcom Commander Gen. Joseph Votel took reporters to the Mideast

There is much about the trip that can't be disclosed for security reasons

The message arrived in my in box several weeks ago. It asked if I wanted to go on an “interesting trip” overseas.

Um, yeah.

I didn’t have a phone number for the sender, so it took a day to find him and say, “Sign me up.”

This past week it all came to pass.

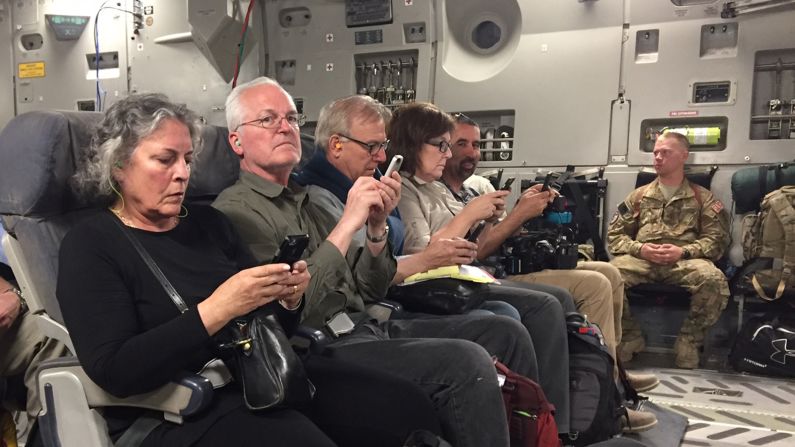

I joined together for the journey with two other journalists, Bob Burns of the Associated Press and David Ignatius of the Washington Post, as well as CNN Photojournalist Khalil Abdallah.

We all met in Tampa and late one night boarded a C-17 transport plane for an overnight flight to our first stop, Kuwait.

We had been asked to make this trip by Gen. Joseph Votel, the new four-star “combatant commander” of the U.S. Central Command. With just a few weeks on the job, Votel is now overseeing the U.S.-led coalition war against ISIS in Syria and Iraq.

No four-star has gone to Syria since its civil war began and no Central Command boss has taken reporters to the front line in nearly a decade.

RELATED: Votel’s unannounced stop in Baghdad

Votel is determined. He tells us there is “nothing to hide.” But of course as is the case with highly classified military and intelligence operations, that’s not the full story.

There is plenty we don’t know and plenty we’re told cannot be reported in order to keep U.S. troops safe. We all signed the seven-page list of ground rules. No journalist wants to have restrictions put on reporting but likewise no journalist wants to put the troops’ lives in danger.

Any reporter embedding with the U.S. military is required to sign similar, non-disclosure agreements based on what type of military units they may be traveling with. These were the most restrictive I have seen. So, you can only guess who we were with.

Despite these restrictions, Votel, to his credit, has decided it’s a good idea to more publicly explain the war against ISIS.

The first part of the journey involves just getting to the region. Votel boards the plane and immediately enters his off-limits “silver bullet” trailer inside the massive cargo hold where he can conduct classified meetings away from those without a clearance. Some of the travel team heads immediately for bunks and even hammocks to get some sleep. But Votel works through the night getting ready for the journey ahead.

Day One: It’s 114 degrees and there are several meetings in Kuwait, a place of relative calm before we move on to Baghdad. We visit a U.S. Army warehouse full of 25,000 weapons ready to be shipped north to Iraqi army.

Then, it’s on to Baghdad. When we land at the airport in Iraq’s capital, there is still one more hop to go. A State Department helicopter flies us to the heavily protected Green Zone as the sun is setting, a 10-minute trip.

Thirteen years after the U.S. invasion, it’s still too dangerous to drive the airport road into town, so air is the only option.

While Votel is in meetings, we tour the rarely seen coalition operations center. We see how targets for airstrikes are selected and coordinated, how the decision to bomb is made. It is quiet and studious inside. Screens have been carefully checked so no classified information is visible to us.

We board yet another chopper.

The next stop is a training base in Taji to get updates on the massive American effort to train and equip Iraqi forces.

And now it’s about to get more interesting.

We’re off to another location. This one we can’t say much about.

We can’t reveal where the base is. We can’t tell you its name, or what type of personnel work there.

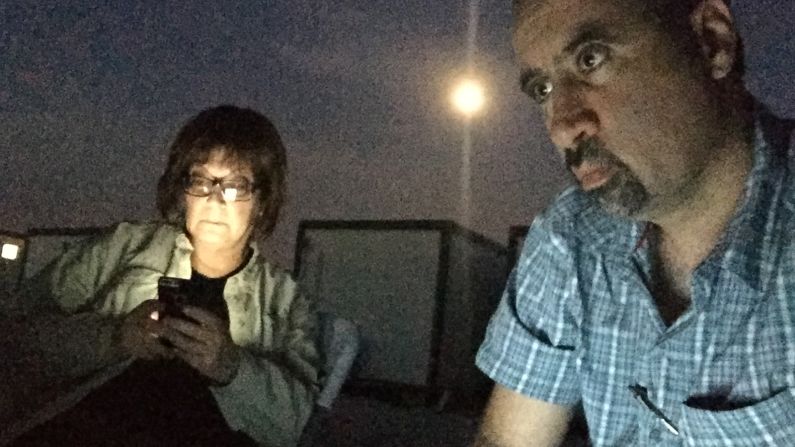

We can tell you there is a very tiny chow line. You hold out your tray, the server says “one per person,” food is dished in, and you move on. At night, we had separate sleeping quarters, so Khalil and I worked on a cot outside under the moonlight.

RELATED: U.S. military officials tout win against ISIS

The next morning, we board aircraft – the type of which we aren’t allowed to disclose – for “northern Syria.” That is the only description of the location we are now allowed to give. We’ve known about this stop since before we left, but carefully kept mum for the safety of all involved, including us. On the ride from the undisclosed base to this place in Syria, we are joined by a heavily armed security team I am not permitted to describe.

Let me pause to say I have ridden military helos around Iraq and Afghanistan for years. The team flying into Syria wins – heavily armed is an understatement.

The reason of course: If our aircraft goes down, we’re not in very friendly territory and we are carrying very valuable cargo – the general and his team. The security team is prepared to fight off any opposition until more help can come.

We land at the base in Syria. We can’t tell you how long it took to get there or describe the terrain, for that could help the enemy calculate its location. We can’t even tell you anything about the base, what it looks like, who the Americans there are. It’s not comfortable for a journalist to be in that situation, but it’s the price of admission to the most secretive trip I’ve ever been on and the chance to bear witness to what is happening there.

Even with the restrictions, we spent the day pushing to report more. We were met with a smile, and a firm “no.”

We literally have dropped off the grid. Our cell phones are off. Our bosses know they won’t hear from us until we’re out. And if you think the place I am talking about sounds secretive, Votel has gone on to yet another secret base. He will come back for us when darkness falls. We are told no more.

We spend the day meeting dozens of local fighters training to take on ISIS. This is the new army the U.S. is trying to train and equip in Syria. They don’t like the fact that ISIS has taken control of large parts of their country and want it back.

It’s fascinating to see first-hand, but we can’t report it until we get out of Syria, so I can once again turn on my phone, computer and Khalil can open up the 300 pounds of gear we had with us.

Finally, we can begin to tell the story to CNN viewers of where we have been, what we have seen, what we have learned. While we still can’t reveal the undisclosed locations, bases, aircraft and commandos who must remain anonymous that made the trip happen, we are glad to be able to share what we can, to show what we can, to give viewers a little better sense of the war than they had before.

At one point on the journey our black backpacks were comingled with the black backpacks of the troops with us. Not paying attention, I pick up the wrong one. I can’t say what I was told was inside, but I put it down gently. Very gently.

Needless to say, the promise of that first email sure was kept – it was an “interesting trip.” Um, yeah.