Editor’s Note: Gene Seymour is a film critic who has written about music, movies and culture for The New York Times, Newsday, Entertainment Weekly and The Washington Post. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

If “Call me Ishmael” is the platinum standard for opening sentences in American fiction, then the following is the single greatest punch line in our nation’s literary history:

“Now vee may perhaps to begin. Yes?”

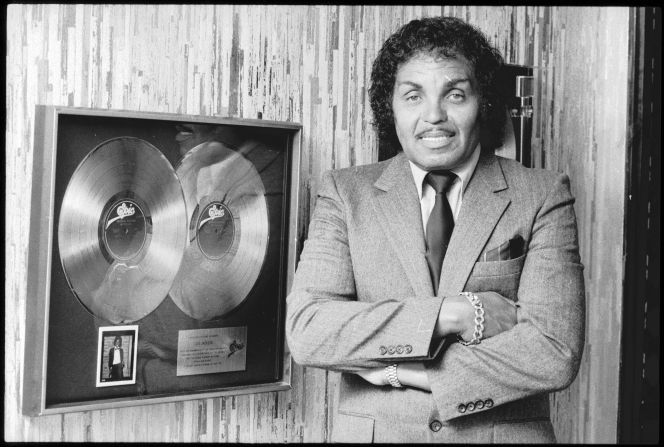

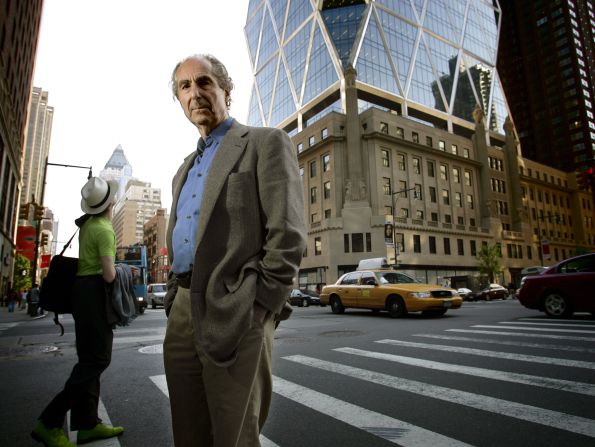

That, as many of you may remember, is the capper to “Portnoy’s Complaint,” the 1969 novel that boosted Philip Roth’s status from elite literary prodigy to best-selling phenomenon.

The query is submitted by Dr. Spielvogel, the psychoanalyst to whom the novel’s eponymous protagonist, Alexander Portnoy, has for the previous several hundred pages poured out his heart and soul in a sustained, wildly free-associating aria of bawdy reminiscence and intense self-loathing.

In similar fashion, Roth’s death at 85 leaves us at the end of a lengthy virtuoso performance thinking somewhat along the same lines as Spielvogel: Now, perhaps, we may begin to know who Philip Roth is and what he left behind.

Which is neither as simple nor as tidy a task as it might first appear, given the depth and breadth of Roth’s achievements – and the furor that often accompanied them.

He seemed to emerge in the 1950s as fully formed a literary stylist as his equally precocious contemporary John Updike. “Goodbye, Columbus,” the novella and short story collection that won the first of what would be several National Book Awards for Roth, was hailed for felicitous writing and evocative portraits of post-World War II Jewish life. Many influential Jewish leaders also reviled it for what they believed were negative depictions of its characters.

They also disapproved of “Portnoy’s” raunchy portrayal of a prototypical “nice Jewish boy” struggling to break free of his parents’ expectations.

Yet the novel and its accompanying critical and popular success shook all restraint from its author, who for the rest of his life took audacious chances both with the flow of his writing style and in his explorations of both self and society. Roth was so prodigious and varied in his output that no shorthand characterization of his work would easily suffice, no matter how many times people would try.

Too often, for example, book-chat mandarins would consider Roth a writer whose only concern were the vagaries of personal identity as he used such alter egos as Nathan Zuckerman and Peter Tarnopol in what seemed autobiographical novels. He always insisted they were more fiction than documentary: “Am I Zuckerman? Am I Portnoy?” he rhetorically (and coyly) asked an interviewer in 1981. “I could be, I suppose. I may be yet. As of now, I am nothing like so sharply delineated as a character in a book. I am still amorphous Roth.”

Yet there was nothing amorphous about the way Roth engaged the world, whether in “Our Gang,” his impassioned, freewheeling 1971 burlesque about Richard Nixon’s administration, or “The Counterlife,” his 1986 tour de force in which his alternate “selves” are placed against a backdrop of tension and terror in Israel and Europe.

And, most especially, the remarkable series of novels he wrote in his 60s, which, in varied ways, confronted the political and cultural history of 20th-century America with both humane warmth and messianic urgency: “American Pastoral” (1997), “I Married a Communist (1998), “The Human Stain” (2000) and “The Plot Against America” (2004), a chillingly reimagined view of World War II America whose reverberations have been felt most keenly in the Trump era.

So how, Spielvogel-like, do we start confronting a body of work as daunting in range and ambition as Roth’s?

Perhaps appropriately with some irony: Back in 1960, when he was still a young literary gun on the rise, Roth delivered a controversial speech in which he said that postwar American reality had become too big, varied and chaotic for novelists to replicate persuasively for their readers. Thirty years later, Tom Wolfe, Roth’s contemporary who died last week, countered by saying, in essence, that novelists, including Roth, had simply stopped trying to evoke what Wolfe termed “this wild, bizarre, unpredictable, Hog-stomping baroque country of ours.”

Leaving aside some of the verbiage, I think Wolfe was wrong when it came to Philip Roth. He did bring America to life for us in the grandest and most intimate terms possible. Assuming civilization lasts long enough to allow us to do so, we’ll be picking up the pieces of his work for closer examination decades from now.

So begin already!