It was 2003, and Leora Krygier was rummaging around a thrift store near her home in Los Angeles.

Krygier wasn’t looking for anything in particular, but a box of old vintage postcards caught her attention.

“I’ve always been interested in vintage and postcards. Nobody sends postcards anymore, really. There’s sort of a beautiful little vintage remnant of the world,” Krygier tells CNN Travel.

She spent the best part of an hour flicking through the box, picking up faded dispatches from locations across the globe and looking at the scrawled messages to family, friends, loved ones.

One postcard stood out among the others.

“I came across this specific one, which looked different from any of the other postcards that I’d ever seen there,” Krygier recalls. “It wasn’t glossy, it wasn’t pretty. It looked like it was mailed in 1942. And it looked like it was some kind of thank you card, from a soldier.”

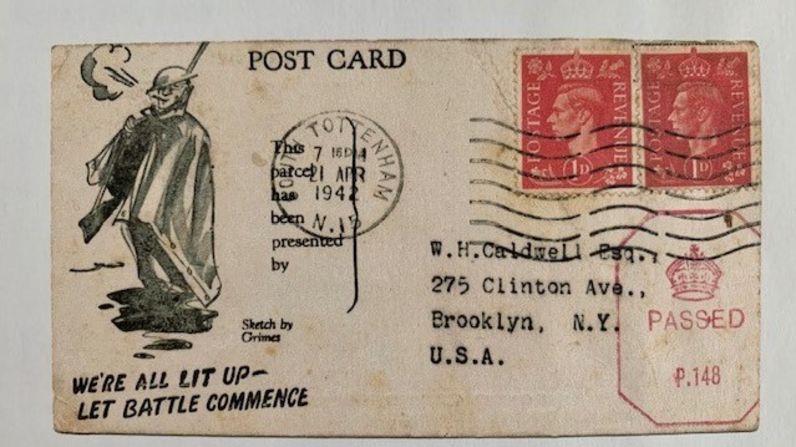

On the front of the faded, sepia dispatch was a sketch of a soldier smoking a cigarette, with the caption: “We’re all lit up – let battle commence.”

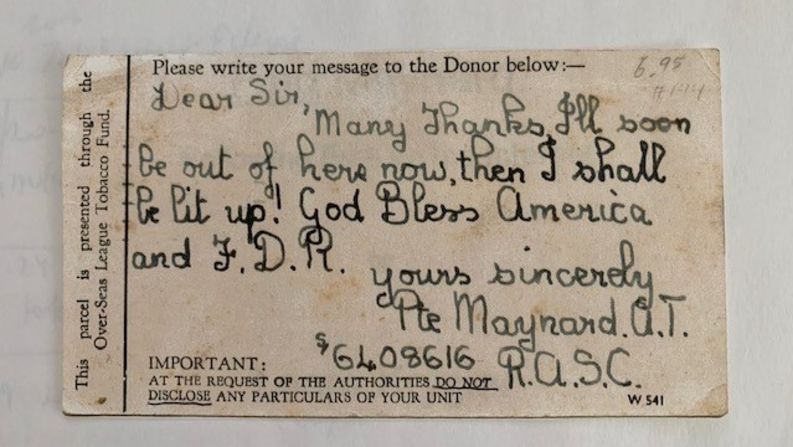

The message on the back was short and sweet.

“Many thanks,” it read. “I’ll soon be out of here now, then I shall be lit up! God Bless America and F.D.R.”

The mail was addressed to a W.H Caldwell Esq, resident of Clinton Avenue, Brooklyn. It was signed by a Private A.T Maynard, a British soldier.

There was a post stamp from Tottenham, London.

Krygier set the box of postcards down. She knew this was the one she wanted to buy. She purchased it for around 50 cents.

Back at home, Krygier examined the postcard closer.

She figured Maynard was thanking Caldwell – for sending him some cigarettes, perhaps? But really, the message prompted as many questions as it answered.

Someone who was a young man in the early 1940s would likely be in their late 70s or early 80s in 2003, Krygier realized. There was a chance that Maynard was still alive.

“I wonder if I could find this person who wrote it,” Krygier recalls thinking.

It wouldn’t be a total stab in the dark – she had his last name and his initials to go on, and his serial number was printed underneath his signature.

And there were the details of the addressee, which could be another lead.

Still, in the early noughties, tracking people down online wasn’t that easy. Krygier couldn’t do a Twitter call-out, and ancestry and family history websites were still in their infancy.

She figured her first port of call should be the British Army. She wrote a letter with the details and requested more information. But she says British Army officials were hesitant to help at first.

“They kept telling me it’s confidential, it’s confidential, we cannot give you any information about him,” she recalls.

Krygier wrote back and asked if they could at least let her know Maynard’s first name.

After more back and forth, the British Army told her that, according to their records, Private Maynard’s full name was Arthur Thomas Maynard.

This key detail confirmed, Krygier’s next step was to consult recent UK census records.

“I basically wrote out, I don’t know, maybe 50, 60 letters to random people who had the same name,” Krygier says. “I told them my only purpose was to return the postcard, not to make any money out of it or anything like that.”

For Krygier, this quest was an intriguing historical project for her to work on in her spare time, she had a busy day job as a judge and lawyer.

And while she really hoped she’d succeed with her mission and find Arthur Maynard, sending letters out blindly still felt like a long shot.

In her research, Krygier also discovered that there was a campaign to send cigarettes to Allied forces via the Over-Seas Tobacco Fund. She figured Caldwell had donated to that campaign, and that’s why Arthur Maynard was writing to thank him.

The cigarettes were sent in packages along with postcards printed with the donor’s address, allowing the soldiers to write and thank donors directly.

Krygier researched Caldwell and found he had British roots. As far as she could surmise, he had no direct descendents. It didn’t seem like that Caldwell and Maynard would have known one another personally.

Over the months that followed, Krygier got several responses from people who thought Maynard may have be their father. It turned out there were a fair few Arthur Maynards who’d fought for Britain back in the war; each one turned out to be a false lead.

But one day, almost a year into her quest, Krygier got an email from Michael and Valerie Boxall, residents of the rural village of Stibbard in Norfolk, England.

The Boxalls was writing on behalf of their neighbor, Tom Maynard, and his sister Winnie Maynard Davis. The two siblings, now in their 80s, had a brother called Arthur Maynard who’d been in the same unit as the letter writer, but who’d since passed away.

Michael Boxall explained he was writing on behalf of the Maynard siblings because neither of them owned a computer, but he did.

He asked if Krygier could send a photocopy of the postcard, so they could try and match the handwriting.

She obliged, and in return the Maynard siblings sent over, via Michael Boxall, an example of their brother’s penmanship.

When Krygier opened the email, she gasped.

“I didn’t even need a handwriting expert, to see that it was a match. It was like a perfect match. Even a lay person could see that. The handwriting was perfect,” she says.

All the dead ends and unanswered letters had been worth it. She’d found Arthur Maynard at last.

An idea began to form. What if, rather than just sending the postcard back across the Atlantic, she delivered it in person?

A transatlantic reunion

In late summer 2004, Krygier packed her bags and boarded a flight to London with her teenage daughter in tow.

Her aim, she says was “closing an arc.” Her family thought she was “a little crazy,” she recalls, but they understood how much the research meant to her.

After arriving in London, Krygier and her daughter took a train northeast of London to the city of Norwich, England and then traveled on to the village of Stibbard.

“My daughter was 16 and it was our first mother-daughter girls’ trip together,” recalls Krygier. “We spent a week in London too where I had rented an apartment and where we tried very hard not to be typical tourists.”

Certainly, meeting Tom Maynard and Winnie Maynard Davis was far from a typical tourist activity.

The encounter was an experience Krygier says she’ll never forget.

“They really treated me like long lost family, and it was so special,” she says.

She also enjoyed meeting the Boxalls, and other residents of Stibbard who’d heard about her quest.

And sitting in Tom Maynard’s kitchen over a cup of tea, Krygier presented the siblings with the almost 60-year-old postcard.

In turn, they filled in the gaps about Private Arthur Maynard’s life.

“I had hoped that I would have found him alive, obviously,” says Krygier. “And it turned out that this soldier, he had a very sad life. He had never married, never had children. But he loved classics. He loved to paint.”

Hanging on Tom Maynard’s walls were some of his brother’s delicate watercolors.

The group talked about Arthur Maynard for hours, showing Krygier his artwork alongside letters and artifacts from his life.

“It was as if this interaction had brought their brother back to life again,” says Krygier.

Before she left, Tom Maynard gave Krygier a few of his brother’s watercolors to take home.

She was touched and accepted graciously.

“It was a once in a lifetime kind of experience,” she says.

Lost in time

For some time afterwards, Krygier kept in touch with the Maynard siblings and the Boxalls.

She enjoyed another visit to Stibbard a few years later with her husband and daughter, and also met up with the Maynard siblings at Winnie’s daughter’s house on a later trip to the UK.

Tom Maynard and Winnie Maynard Davis have since passed away, but Krygier remains in touch with the Boxalls via the occasional email and annual Christmas cards.

Following the Maynard siblings’ deaths, Krygier isn’t sure what happened to the postcard. Although Krygier met Winnie Maynard Davis’ children, she’s not in touch with them anymore.

“Did somebody in the family, take it, keep it, throw it away?” she wonders. “It’s just a really small postcard. It could easily have disappeared from the face of the Earth.”

But Krygier doesn’t mind if the postcard’s been lost in the ether.

“That’s the way things are sometimes,” she says.

After all, now Maynard’s legacy extends across the Atlantic to Los Angeles, where some of his watercolor paintings hang on the walls of Leora Krygier’s home.

And finding the postcard also prompted Krygier to embark on her own family history quest.

“When I first visited Tom we had many wonderful conversations about life and family,” she says. “He asked me if I had researched my own family tree and it suddenly occurred to me that I hadn’t. I realized then that perhaps this year-long research into a random stranger’s story was my circuitous route towards research into my own family history and the threads that wove into my own life.”

Krygier’s father was a World War II Holocaust survivor who left Europe in the 1940s. He met Krygier’s mother at the opera in Israel. Krygier was born in Israel and the family emigrated to the United States when she was young.

“I realized that much of his persona and behavior as husband and father was bound up in his history as a Holocaust survivor, something I didn’t really understand growing up,” says Krygier.

Krygier has written a memoir which explores how the postcard mystery led to a subsequent dive into her family’s past. “Do Not Disclose” will be published in the US in August 2021.

Today, Krygier is still fascinated by old postcards, and enjoys following social media accounts that post snapshots of old mail.

And with her research into her own family tree more or less concluded, Krygier occasionally ponders sifting through a thrift store and making a new postcard the center of a quest.

“It took so much of my time and energy that I don’t know whether I would actually do it again, but I have thought about doing it,” she says.

“Because it was a wonderful journey, and you know, sometimes just random things are just so amazing in life.”