Two walls have brought me to tears. They are on opposite sides of the world, 8,600 miles apart. Both are filled with names of people I never knew but who have helped shape the person I have become.

The first of those walls is the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial in Washington, DC, where 140 black granite panels are etched with more than 58,000 names of US soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen killed or missing in Southeast Asia between 1956 and 1975.

When I first visited it in the early 1990s, standing at its deepest point gouged in the DC earth, I cried for the youth and the promise lost, and at the realization that but for the randomness of birth dates (I was too young to go to Vietnam) my name could have been on that wall.

I saw the second wall in 2019. It sits in a village in Vietnam more than two hour’s drive from the booming, busy city of Da Nang in central Vietnam. Vietnamese call the village Son My. Americans call it My Lai.

In November 1969, what happened at My Lai sprang into newspaper headlines in the US and around the world when an article by journalist Seymour Hersch hit the wires.

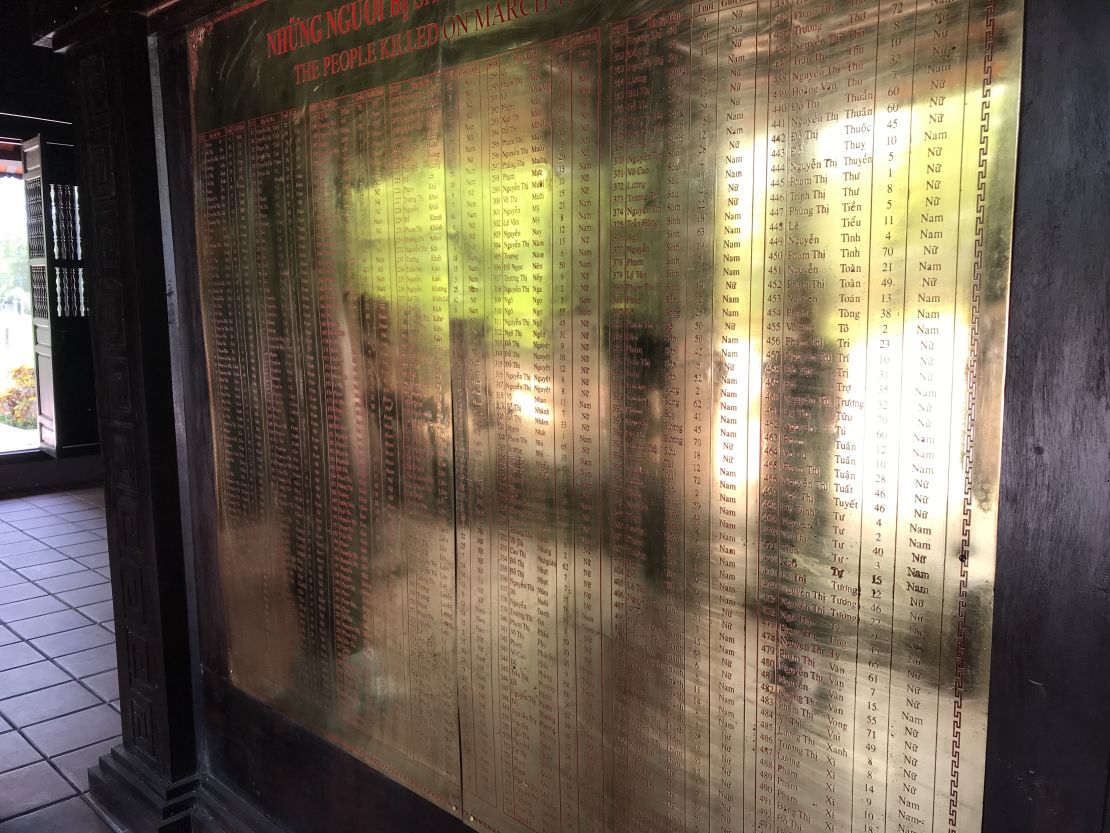

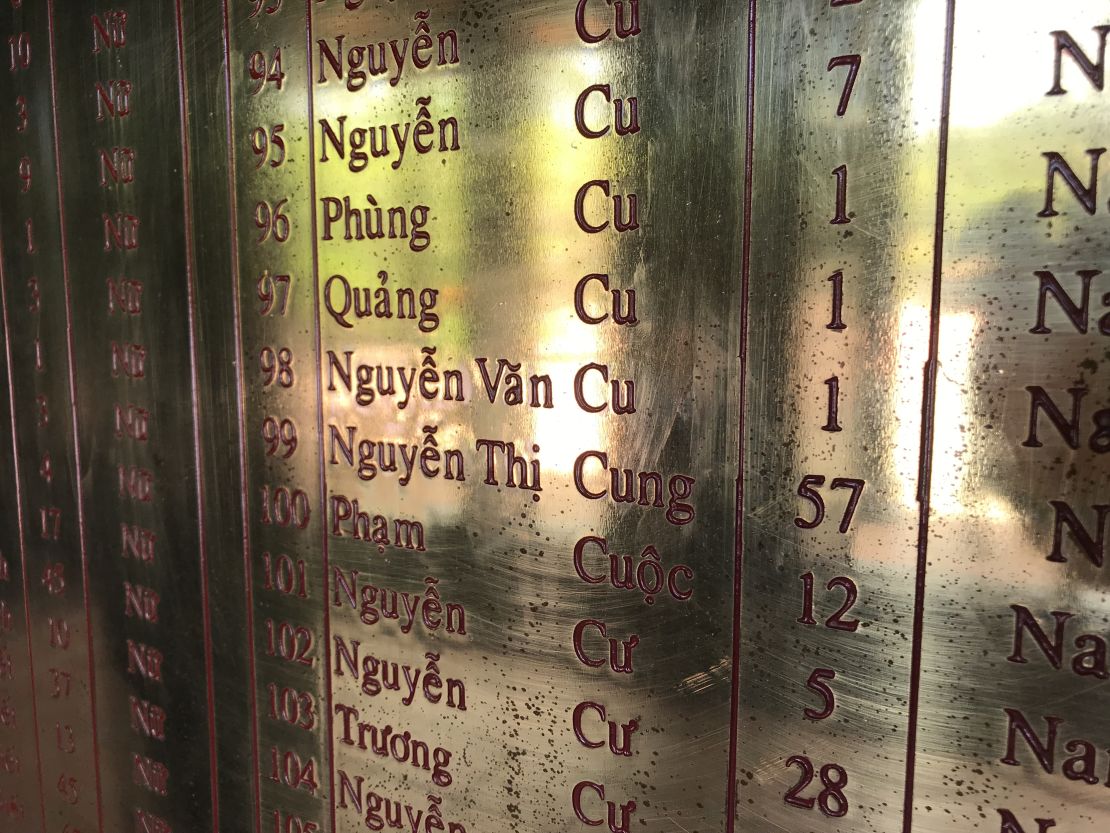

More than 500 names are on the wall at the memorial in Son My, all of them people, several as young as a year old, executed by US troops on March 16, 1968.

The US military kept the My Lai massacre secret for 18 months.

But when headlines on My Lai hit newspapers in November 1969, it put new vigor into the anti-war movement in the United States. US troops got tagged “baby killers” as anti-war protests spread across the country. They would eventually lead to the withdrawal of most US forces three years later, and the reunification of North and South Vietnam under the Communist government in Hanoi in 1975.

My memories, even as a 10-year-old in 1969, are vivid. The pictures, taken by a US Army combat photographer, were horrifying. Piles of bodies, looks of terror on Vietnamese faces as they stared at certain death, a man shoved down a well, homes set ablaze.

These were not the US soldiers who liberated Europe just over 20 years earlier, those GIs I’d seen in popular TV shows like “Combat!” and “12 O’clock High.” Americans didn’t do this kind of thing. Nazis did.

Five decades later, those black-and-white scenes of the 1960s appear before me in color in central Vietnam.

Pulling off the main road and heading toward the Son My memorial, we wind through a village where very little could be called modern. Homes and shops are open to the street. The ubiquitous scooters are parked out front or squeezing alongside our SUV on the narrow road, frequently beeping their horns to warn car drivers of their presence.

The vivid red-with-yellow star Vietnam flags hang from many businesses and homes. These few weeks are a time to honor the country’s soldiers, our guide says.

Arriving at Son My is almost a surprise. There’s a sign, but it doesn’t blare out, “war atrocities committed here.” A lone tour bus is in the parking lot, pushed to overhanging trees at the very edge to keep it manageably cool in the blistering sun and heat of Vietnam.

A few Western tourists walk among the My Lai village exhibit. Like us, they look at the markers outside the ruined foundations of the houses that stood here on March 16, 1968.

“House of the Do Phi’s family restored after being burnt down by US soldiers on March 16, 1968. Five member of his family were killed.”

Then the ages – 57 the oldest, 2 the youngest.

We walk into “artillery shelters” built across from some of the ruined foundations. They are L-shaped mounds of earth and concrete, too small for a 5-foot-9 American to stand up in, and maybe 10 adult steps lengthwise. Five, 10, a dozen people would crowd into one when US shells fell on the village, our guide says.

As we walk, what were once dirt paths below our feet are now cement, but with the history of My Lai sculpted within them. There are the barefoot prints of villagers as they would have been on a damp morning. Bicycle tracks crisscross the footprints. And then, the unmistakable prints of American GI combat boots.

The paths lead to a watery ditch at the edge of the village, a field of rice at its end.

It’s late morning, and the air is heavy, quiet and still.

The ditch is a few yards across, maybe a football field long. There’s a marker on the far bank.

“This ditch reminds that US soldiers captured 170 villagers and pushed them down this ditch then shooting them dead on March 16, 1968.”

I’m shaken. The news clips of my childhood are replayed in my mind.

Beyond the ditch, sits a shrine to the dead of My Lai. I get lighted incense and place it in the urns on the altars inside. Sadness and shame well.

At the front of the shrine sits that second wall, a golden one. The names of all the My Lai victims are inscribed here, followed by their gender and age.

This is where the tears can’t be choked back. My own reflection on the gold looks ghostly, asking me for answers I don’t have. It takes me quickly back to that Vietnam Wall in Washington and what I felt decades ago.

Taking a photo of the whole My Lai wall doesn’t seem possible. It’s as if the gold nestles the names, protecting them with light, giving them a place to hide from the horror they saw.

I get up close to get a detail shot. Three ages come quickly into focus – 1, 1 and 1. Tears cloud my view of my phone screen. I walk away to the museum beyond.

The facts, as Vietnam sees them, are in that museum. They present a compelling argument that US forces entered My Lai on that morning, intent on wiping out a village of non-combatants – old men, women, children, those three 1-year-olds.

US military accounts don’t deny the event, though death tolls differ. Some American accounts will tell you My Lai was a village that harbored and aided Viet Cong guerrillas who’d been responsible for dozens of US deaths in the area. Some US soldiers who shot those civilians testified that they were under orders to kill everything in My Lai.

But other Americans ignored those orders. Some, in fact, even turned their guns to face their countrymen and protect fleeing Vietnamese.

Of the scores of Americans in My Lai that morning, only one, Lt. William Calley, was ever found guilty of a crime. Despite receiving a life sentence for murder at a 1971 court martial, he saw it reduced and was eventually paroled after serving only three years.

Many in Vietnam – and in America – decry that as an injustice. But our guide tells us ill will doesn’t linger. Vietnamese look forward, not back, he says, reassuring us that Americans are welcome in 21st century Vietnam.

But as I look back at my photos of that golden wall, I see the shadows looking back at me.

And my throat tightens. And my eyes well.

If you go: Vietnam’s borders are now closed to international tourists due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Those currently in the country can book trips to My Lai online or at local travel offices through a variety of operators. Prices range from about $70 to $120 per person, depending on departure location – Hoi An or Da Nang – and include other stops in the package.

This story has been updated and republished to reflect time changes.